the vertical

random sharing

I am not being touched by the essence and the meaning of public celebrations usually – the New Year, Saint Valentine’s Day, Easter, etc. The main ideas of these celebrations and the dates representing these ideas mostly quite disagree with the rhythm of my body. I am rarely eager to “squeeze” love out of me on Saint Valentine’s or to revive during Easter. Yet I adore celebrating silent victories against myself – the reading of a fundamental book, comprehension of a complex theorem, creation of a good composition, etc.

This also applies to silent challenges for myself on the way: I am always willing to give a meaning to them, to mark them in some way. Giving some importance to the upcoming challenges would allow to better recall the way I sensed before addressing a complex objective. Probably, this is why I faced one of the greatest challenges in my life wearing my most expensive shirt and shoes. I wanted to give a meaning to my fight of the fear of the upcoming challenge and to meet potential hardships awaiting me with pride.

I was travelling to England with 1,000 pounds in my pocket to study the Masters of Electronic and Computer Music and overall to conquer this land. A situation not over contextualised or significant in any way at first sight – just like another subplot in Marius Ivaškevičius’ play Išvarymas (Expulsion) about emigration. Yet it was not that simple as I was responsible for two other women, one of whom was just one-year-old. They were jo join me and my plans of conquering the world in the island in a month’s time, so I had to materialise my determination and energy quickly.

The conquering of the island was to begin in Leeds – United Kingdom’s third largest city by population (after London and Birmingham), which is located in the middle of the island. Because of my limited finances, I was planning to start my existence in England with living in a tent. However, rainy weather in Lithuania the last night before the trip somewhat suppressed my desire to subject my body to living in similar conditions on the island. So the last night I booked a hostel for just ten pounds or so per night, which was located in the village of Haworth some 30 kilometres from Leeds.

The island reacted to my most expensive shirt with a hysteric laugh: as soon as I landed, I found myself in the middle of a storm. As I booked the hostel in the remote village as late as the night before, I had not enough time to find out how to get to it. By asking people and changing means of transport, I was approaching my destination somehow. Midnight came unnoticed though, while I was standing in the rain, at a distance to my destination of slightly less than ten kilometres.

I had no way out of this situation other than pulling my suitcase weighing almost 30 kg, carrying a heavy guitar case, which contained my guitar and countless household appliances in addition, down the narrow roads of the village in the storm. Shortly, my suitcase ripped, and raindrops were dripping from me all over. Angry, I started questioning my existence on the island and my belief in what I was doing there. For the first time, my mind realised the odds I will have to play against while in England. I thought that I was in danger of getting remote from music and that the island’s inhospitableness might bring me to some factory to be able to survive.

Nevertheless, both that and other nights, one context that I have already mentioned in my stories was leading me further. A great Lithuanian musician and music critic, Domantas Razauskas, during one of his concerts, gave a comparison which is close to my philosophy. He said, take a forest full of trees. It seems, nothing makes those trees interrelated; however, the roots of some of them are intertwined particularly closely. Sometimes, even quite remote trees can have roots intertwining closer than the roots of those growing nearby. According to Razauskas, in a similar way, people, too, are related with one another through invisible bonds in the physical world. Consequently, even people who are very remote one from the other (in every aspect: cultural, social, geographical, etc.) can have much more in common than some two people living close by.

Yes, my mind did perfectly realise all the odds I will have to fight, but I did not cease to strongly believe that I was interrelated “through roots” with some of the local people. The people who will comprehend all the contexts I am bringing, who will give me an impulse, and will help me tame this island.

In this specific situation, I defined for myself ‘belief’, making use of the above-named concept of tree roots. Yet it seems to me that each human being has a secreted adaptation of the dilemma of belief in their life, in the areas they operate in. Those adaptations do not necessarily have to relate to religion, God or similar concepts in any way. For example, in the philosophy of mathematics and in mathematics in general, one of fundamentals issues dealt with, one of fundamental dilemmas is: Does mathematics exist independently of man and the man just discovers, reveals those laws of mathematics that exist by themselves or does such absolute independent mathematics not exist at all and the man just creates it little by little, theorem by theorem?

It seems to me that this underlying mathematical issue is nothing but a sophisticated adaptation of the dilemma of belief and of belief in God in general in the mathematical context. Now, for instance, supporters of the independent existence of mathematics (also known as representatives of mathematical platonism) basically take up the same position as those who believe in God: There exists something independently of us, something we are too little to perceive, to see or to comprehend.

A year ago, I happened to talk with Rimas Norvaiša, a Lithuanian mathematician and philosopher of mathematics of the older generation, about his approach to the above-named mathematical dilemma. According to him, he began his career in mathematics believing that mathematics exists independently of man, but, gradually, he found himself on the opposite side of the barricade. Indeed, most people I know, irrespective of the adaptation of their dilemma of belief, have almost an identical approach to the dilemma of belief as Norvaiša. In the early stage of life, people believe until they become older when they gradually take up the opposite position. Such approach to one’s own dilemma of belief has always seemed logical to me, but not completely right. The conception of belief of the politician and theologist S. she shared with me answered many questions I had about the approach to one’s own belief.

S.’s conception of belief is inevitably associated with the central symbol of Christianity – the cross. When I talk or discuss about belief, I usually avoid using any keywords associated with some specific religion, such as Jesus, Muhammad, Koran and the like. I also try not to use general words that are often encountered in the contexts of religious studies, such as sinful, Lord, etc. I notice that the use of these keywords very often enrages people and prevents most discussions on the topic of belief. I avoid these contexts not only because of other people, but myself as well. I, too, find such keywords and contexts too straightforward, unsubtle, unsophisticated, and incomprehensive in the context of the dilemma of belief. Similar to some of the nightmarish Hollywood films that are only capable of invoking zombies, guns, death or other similar themes to depict evil. However, S.’s conception of belief is so putting everything in their place that it would be a shame not to include it in here.

According to S., the cross can be interpreted as follows: its vertical (longer) part represents the world as it should be, while its horizontal (shorter) part represents the world as it is. To cut the long story short, comparing the lengths of the two parts of the cross is turns out that, in the real world, there will inevitably always be much less positivity, happiness, joy and logic than there could/should be. While every human being is hanging on the cross point of the vertical and horizontal lines all their life and the way they, hanging there, cope with this proportion: The world is as it is/The world as it should be, is a belief.

Why is this conception so important and how does it relate to the contexts I mentioned before?

I tend to believe that the absolute majority of the adaptations of the dilemmas of belief contain not just belief, but expectation as well. For example, a large proportion of believers in God prey for a good fortune for themselves and their environment. Yet, when such good fortune for them and their family and friends never happens, such people begin losing general belief in God. Or, for example, a large proportion of people supporting some football team do expect a victory for it and a fun time for themselves at the same time. However, if the team loses steadily, such people gradually give up belief in that specific team. Consequently, that, although small proportion of expectation in general belief, over time markedly weakens general belief in something as well.

Meanwhile, S.’s concept is an absolute nugget: it consists of 100% of belief and 0% of expectation since the essence of this concept is that it is always worse than it should be, so there’s nothing to expect.

To revert to my trip, my belief during the trip as an expression of the above-named tree root concept undoubtedly contains a very high proportion of the expectation of specific benefits for me as well. Yet my aim should certainly be proceeding to S.’s above-named conception – belief without a grain of expectation. I guess, I should demonstrate my solidarity with the fans of Lithuania’s football team at some point:)

I reached my hostel as late as 3 o’clock in the night, knocking on its door and waiting for someone to pick up the phone for another half-hour. Next day after the nightmare night, I felt more dead than alive. Nevertheless, towards an evening, I went out to look round and was totally enchanted by this idyllic English village. It turned out that Haworth is famous for the fact that the world-famous writer Charlotte Bronte, mainly known as the author of the novel Jane Eyre, lived, wrote, and died there. Inspired by this fact and with relatively much time at my disposal left from the search for accommodation and submission of the documents for my studies, I spent a good couple of weeks wandering around Haworth and writing. It was in Haworth that my story Questioning published on this site, saw daylight.

No less than Haworth, I was impressed by the hostel I was staying at. Despite its extraordinarily low cost, it was housed in an ancient Victorian manor house with stunning aesthetics. This experience was my first coming in touch with one especially remarkable phenomenon of England.

England has a network of hostels known as YHA (Youth Hostels Association). This network’s hostels (joining about several hundred hostels), as in Haworth, are established in ancient manors, castles, barns, and other special venues. This network is a charity organisation which gives all of its profits from accommodation namely for the restoration and maintenance of buildings of the ancient architecture. Accordingly, the clients of this network are given an opportunity to stay in these exclusive buildings with incredible aesthetics for a relatively lower price than such an opportunity would cost on England’s market.

Staying in YHA network hostels and concurrently travelling England’s remote villages and nature allowed to dispel one myth for myself. By then, when someone would utter the word “England”, I had pictured the rainy and dirty streets of London or such an industrial city as Manchester in my mind. It had never occurred to me that England is rich in such spectacular locations or small villages as Lake District, Whitby, Robin Hood Bay or Malham, which, at least in terms of my sense of aesthetics, are just as good as the masterpieces of nature such as Iceland, the Great Canyon, etc. The word “England” now summons up quite different images in me. Images that are closer to England’s real origin – its nature, villages, shepherds, sheep, etc.

What thrills me is not just the nature of that distant island, but also the way England’s ordinary people have made it serve their lives. Even in most remote villages or natural sites, you will always find remarkably cosy pubs full of intelligent random visitors, top quality beer, and England’s minimalistic masterpiece – fish and chips. The whole of English nature and the way it has been made to serve people’s lives had captivated us so much that after we “conquered” the island to a certain extent and autumn depression surrounded us, the entire autumn we went incessantly through the same routine: on Friday evenings, we would finish our works, hurry to the Leeds train station, and head to some remote English village before returning back on late Sunday or Monday. Neither then, nor now can I think of anything better on Earth than to spend the whole day walking, thinking in the rainy mountains, and sipping beer or wine, and reading a good book or writing such stories as this in a nice pub in the evening.

I was staying in the Haworth hostel not alone: the living premises accommodated eight beds. During the few weeks I spent in the YHA hostel I thus happened to socialise with countless most different random visitors. Nevertheless, during the entire two-week period, I consistently, day after day, was keeping a close contact with just the few people who shared the living premises with me.

One of them was a young man of Pakistani origin aged 25-27, who introduced himself as a former major organiser of the drugs business around Bradford. Bradford is a Great Britain’s city over ten miles away from Leeds and is known as one of the cheapest cities to live in with the highest record of criminal offenses and one of the largest Muslim communities in the country. Bradford was especially relevant in our plans of “conquering” the island since we planned to settle in it at the beginning of our journey. Incredibly cheap accommodation, a short distance to Leeds, and the fact that L. had to exchange the Vilnius Academy of Arts into the Bradford College because of her exchange programme made us take such a complex decision for us. What was even more exotic, my above-named roommate from Bradford had his arm broken and, he said, he had chosen staying at the remote hostel in Haworth until everything “settles down” after the incident related to his injury.

When I am writing this story, all this (my living conditions, my roommate, Bradford, etc.) seems like a really intense and dangerous way of living, but at that time all seemed much more simple. Probably because, at that time, I could not avoid such contexts or roommates and had to take this as an inevitable reality on the way towards conquering the island. Moreover, the situation was much less awkward than it looked: the roommate fascinated me from the first moment I saw him by his sincerity and not hiding his life activities. So, almost daily, we lunched with him and his wife, who used to bring him warm food from Bradford. For a man who has nothing to do with the criminal world, it was interesting to hear about such contexts and experiences. Not just interesting, but – at that time – especially useful, as I learnt about all most dangerous areas, streets and even houses in both Bradford and Leeds, which had a direct impact on my search for accommodation.

As my stay in the Haworth hostel was coming to an end, a friend of that roommate moved in our room, who looked like a typical criminal and had the same motive of living in a remote hostel – “to wait until everything settles down”. The representatives of the hostel which was more and more used for such purpose got worried and decided to voice their position to my roommates. Thus, the stay of those two roommates in the hostel in Haworth ended both quickly and peacefully, by mutual agreement.

Another close roommate of mine was an American about 55 years old, who spent most of his life working on engineering projects across the world. During one of his projects in South Africa (which took place during the World Football Championship hosted by South Africa, in 2010), he decided to quit all of his works, to sell out all of his belongings, and to set off on a journey around the world with just a small rucksack. We laughed a lot at his pictures where he was standing in the South Africa’s capital, Cape Town, near his hotel, selling his luxury belongings for a dollar or so a piece – cloths, shoes, etc. Meanwhile, locals were surrounding him and their faces in the photos are showing that they don’t really get what’s going on.

I was touched by one of the first talks with the American when I told about my situation and my philosophy. About the fact that I was going to combine such fields as mathematics, music, tap dancing, music technologies, that I was responsible for some other people – my family, that I had limited resources for my plans to conquer the island, etc. The American said that one must have ‘big balls’ to behave the way I did. According to him, everyone in such a situation would probably behave contrary to me: it would be much easier to choose the path of specialist, to avoid combining such seemingly non-profitable spheres, and to stay in some calm place until the children grow up.

It was at that moment that the American induced in me a long, rational discussion about the differences between the existence of specialist and generalist (i.e. combiner of many spheres) in nowadays’ social context.

The Chinese philosopher, logician and mathematician Hao Wang, in his book From Mathematics to Philosophy, singles out three very clear and big advantages of choosing the path of specialist. First of all, a specialist can very easily become part of their specific professional community in which they would be able to discuss any issues of concern and be heard generally. Being part of one or another community sooner or later leads to recognition. Such recognition will not necessarily bring the Fields medal (the most prestigious award in mathematics) or another similar award. A person may feel satisfied enough if assigned the title of “head of of some circle” by the community. Each of us wants to be appreciated and often the mere fact of being appreciated by someone overshadows the meaning, context, and level of such appreciation in the world. Finally, the third advantage is just relatively easy securing of one’s survival on this Earth: society will always be determined to share common wealth and general good with a specialist since this is easier than spending several years to master some specific field.

Wang thus holds the view that a person who chooses the path of generalist will, as a huge probability, live in high social exclusion. Which is quite logical: How else could a person without recognition, funds, and people who would be interested to hear that person be specified? Nevertheless, Wang also presents several historical examples of people who did manage to comprehensively master a number of spheres, combine them, and eventually earn recognition as brilliant generalists. One of such examples is Bertrand Russell mentioned occasionally in my stories on this site, who managed to combine mathematics, logic, philosophy, literature, politics and finally was even awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

While realising the rationality of the path of specialist and feeling, experiencing the dangers of social exclusion, I believe that the path of generalist is nevertheless a thousand times closer to me. A shudder to think that, if, at that time in England, I would not have dared combining mathematics and music, I wouldn’t have a happiness now of touching such areas as sonification of mathematics (expressing mathematics with sounds), electroacoustic music, etc. Overall, I think that the general aim of science should be revealing and demonstrating all possible links in this world. And in no way should the key goal of science be seeking for isolation, separation of the processes from their broader contexts. Probably this is why I enjoy identifying mathematical laws, theorems in my social life. For example, in my story For Myself, I applied in a particularly charming manner the principles of Euclid’s The Elements to define for myself the concept of ‘personality’.

However, at this point, Wang does not really agree with me. In his opinion, one should not try recognising scientific laws in social contexts. The Chinese philosopher is not impressed by human efforts to apply Einstein’s relativity theory to support the position that human rules of ethics are also relative and conditional. Or that the evolution theory in biology could prove the competitiveness of modern capitalist society. Wang holds the view that such application of science is somewhat ambiguous and not quite accurate.

I fully agree that such application of science in the analysis of social laws is not quite precise. It seems to me, however, that such use of science in social contexts often brings more life, discussions, and meaning than a most precise use of scientific laws in corresponding narrow scientific contexts.

The path of specialist is light years distant for me due to one more process that Wang mentions in his book From Mathematics to Philosophy. In Wang’s opinion, there exist two types of professions – sick ones and not sick. The aim of the developers of sick professions is to make some vague, unclear theory, arising from artificially raised meaningless issues, a most comprehensively defined profession as soon as possible. And, most importantly, the aim of such developers is to permanently emphasise that their mental product is not at all a theory, but a profession. The purpose of doing so is to prevent people who will analyse that theory from concentrating on its meaningless underlying issues, the artificial context of its occurrence, but instead getting lost in the endless specifications, extensions and details of that theory. By twisting and turning through the labyrinths of such profession, people contribute to promoting the field itself and its developers. Indeed, the body’s reaction to the analysis of some theory is quite different from its reaction to the analysis and cognition of some profession. Theory is a questionable thing, whereas profession is almost not.

In my view, nowadays, sick professions have begun outnumbering ‘healthy’ ones. A considerable number of professions, e.g. couching, can easily be identified as sick ones. Nevertheless, in my opinion, there are a significant amount of professions deep-rooted in society whose underlying issues and main theories have features of a sick profession. Hence, upon choosing to become a specialist in some specific profession, there is a major risk of realising, in a five years’ time, that that specific profession is sick. At the same time, bearing the flag of that profession throughout one’s lifetime becomes senseless.

Generalism basically protects from the danger of all sick professions, since generalists do not become liable to one sphere: they can always transfer the best features from a certain field to another, more stable sphere. In other words, for a generalist, spheres are nothing but pieces of Lego they can model, construct or deconstruct in order to attain their end.

At this point, I will probably finally answer the question you might have by this time: How to identify whether I am a specialist or a generalist?

I know a great many of medical persons who, having been asked to explain some specific medical processes or a specific disease, say nothing but “Don’t you interfere – this is medicine” or “I, as a medical person, already got off work, it is now my free time”. I also know many programmers, financial analysts, managers who, if asked to explain some specificities of or concepts in their field of work, would just say, “These are very complicated processes, you will not understand”. Yet I also know that I could discuss about my spheres – mathematics, music, and science – with people until six in the morning (or even longer, if quality drinks and food are beside:) ). The possibility of explaining to people during such discussions the most complex processes in my spheres brings me an even greater catharsis. Making use of another thought of Wang’s, all I can thus say is: If you apply your knowledge within only a defined time, at a defined place, and to a clearly defined group of people – you are definitely a specialist. If you don’t feel such limitations in your life – you can be called a generalist.

Not even the very best specialists and greatest generalists would be able to convey the joy I was overwhelmed with when I eventually found a home in Bradford. It was no miracle at all – just an ordinary house for a few hundred pounds on the outskirts of Bradford. However, the initial feeling that I owned, in this probably the most nightmare city in the unwelcoming island, a large several-floor house, where you can hide away from the mischiefs of Bradford and of the entire island, gave me a certain inspiration indeed.

We were slowly being taken over by the corresponding environment of Bradford. Huge cultural, social differences between us and the Muslim community we were completely surrounded by began surfacing since the very first day. Initially, I found it rather difficult to understand the underlying reasons for this huge dissonance between us and Bradford Muslims. Yet, once in Bradford, I decided to analyse the existing Muslim community more thoroughly and to try to explain to myself rationally and argumentatively why it is so distant to me and what I did not quite understand in that dissonance. Also, why is it generally important trying to explain to oneself distant and incomprehensible processes? Achilles and The Tortoise will definitely answer you this question.

I am certain that the absolute majority of you have heard about the paradox of Achilles and The Tortoise. Probably under a different title; you might know it as the paradox of the human runner and the snail, or still other titles. You are well aware that Achilles (or just any human runner) will never manage to catch up with the tortoise if the latter starts its distance at least a few meters ahead of the runner. Say, the tortoise is ahead of a runner by a couple of metres. Now, it will take the runner some time to run that distance of a couple metres. During that time the tortoise will have advanced a few centimetres more. Then it will take more time for a runner still to move forward by these few centimetres, while the tortoise moves ahead at least some millimetres more during that period of time. By the time the runner will advance those few millimetres, the tortoise will have advanced at least a microscopic distance. And so the runner or Achilles will keep catching up with the tortoise, but he will never succeed, as, whenever the runner or Achilles will arrive somewhere the tortoise has been, the latter will have moved ahead at least a minimal distance:)

Most of you will certainly cry out, “This is impossible!” Nevertheless, if asked to explain this paradox, you would probably say you should think of Achilles’ and the tortoise’s specific speeds and draw the straight lines of the distances made by Achilles and the tortoise in a time scale. In that scale, you would see very clearly that the distance covered by Achilles very soon surpasses the sum of the distance covered by the tortoise and its minimal starting-point advantage. So, where do I nonetheless see an issue here?

The problem is that you would so explain just the part of the paradox you understand – the paradox’s incorrectness. Yet you can’t deny that even after the above-named graphic explanation, reading the paradox again, it intuitively seems credible nonetheless. In other words, you understand and can explain that the paradox is wrong, but you don’t understand where its intuitive credibility comes from.

Bertrand Russell explains the origin of this paradox stunningly accurately. This British philosopher, mathematician and logician states that the secret of Achilles and The Tortoise lies in the set theory. This branch of mathematics considers two different sets to be equal (or: to have the same cardinality) if the members of those two sets can be paired so as each element of one set is paired with exactly one element of the other set, and each element of the other set is paired with exactly one element of the first set (in mathematics, such pairing is also known as bijection or one-to-one mapping).

This is really easy, but in case you have not fully understood when, in mathematics, two sets are considered to be equal, here is an even simpler explanation. Imagine a dance class, with a girls’ line-up and a boys’ line-up. If each girl is paired with exactly one boy, and each boy is paired with exactly one girl, and neither free boys nor free girls remain, we will certainly say that both sets – of boys and of girls – are equal (or: have the same cardinality).

Why did I elaborate on so simple a concept of the set theory?

When analysing easily countable sets such as those of five girls and five boys in the above-named example, we know by intuition that such two sets are equal. The fun begins when we start analysing sets of a cardinality that is not so easily countable.

What does your intuition tell you: Are there more natural numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, etc.) or even natural numbers (2, 4, 6, 8, etc.)? I suspect most of you believe that the set of natural numbers is larger. However, these two sets are considered to be equal since each natural number can be paired with an even natural number and, vice versa, each even natural number can be paired with a natural number. Here is an example of such pairing: 1→2, 2→4, 3→6, … , n→2n, … .

It is similarly tricky for our intuition to also catch on to the context of real numbers. Let’s say, we have two intervals (two sets of real numbers): one from 0 to 2: [0;2], the other from 1 to 2: [1;2]. Both intervals definitely comprise a great many of real numbers. For example, the first interval comprises real numbers such as 0.1, 0.86792, 1, 1.756, etc. The other interval is also rich in numbers such as 1, 1.222627, 1.5, 1.9999999, etc. However, if you were asked to guess in which interval [0;2 or [1;2] there are more real numbers, what would you answer?

As in the above-named case of natural numbers, this also holds true: intuition suggests that there should be more numbers between 0 and 2 than between 1 and 2. However, as in the previous case, these two intervals contain an equal number of real numbers, as the real numbers of both intervals can be subject to the above-named pairing, i.e. bijection.

So, finally, how does this set theory relates to Achilles and The Tortoise?

Let’s say, Achilles is twice as fast as The Tortoise – his speed is 2 metres per second, while that of The Tortoise is 1 metre per second (we could think of more realistic speeds, but this will make it easier to understand). Let’s also suppose that The Tortoise has an advantage of one metre ahead of Achilles. It is becoming clear that Achilles will have moved forward 2 metres after a second and The Tortoise – one metre after a second; however, given The Tortoise’s initial one metre-advantage, the two will find themselves at the mark of two metres after a second.

In this example, the paradox of Achilles and The Tortoise would be exactly an effort to pair the real numbers within the [0;2] period with those within the [1;2] period. In other words, it would be an effort to pair, at absolutely each fraction of the second, the distance made by Achilles with that made by The Tortoise at the same fraction of the second (including The Tortoise’s initial one metre-advantage). And, certainly, at such countless moments, such pairing would result in a real number within the [0;2] period to be at least minimally lower to the real number within the [1;2] period. Yet, eventually, such pairing would nonetheless end up in the pair 2→2; in other words, at that moment, exactly after a second, the distance made by the two racers would become equal.

Hence, our brain – perhaps not directly, but at least on a subconscious level, perceives that the essence of the paradox of Achilles and The Tortoise lies exactly in such pairing of countless real numbers within different-length intervals. Nevertheless, our brain and intuition deny that real number intervals of two different lengths contain the same amount of real numbers – the longer interval still seems to contain more real numbers than the shorter one for our brains. Our brain and intuition therefore try to reject the fact that a moment will inevitably come when the last real number within the first interval will become equal to the last real number within the second interval (as in the case of 2→2 in the example mentioned above), and Achilles will catch up with The Tortoise.

So, where does this long unravelling of the paradox of Achilles and The Tortoise take us to?

I reckon that we can explain processes that we understand or processes that are just close to us (I mean any context: social or scientific) mostly relatively easily. In the case of the paradox of Achilles and The Tortoise, it is very easy for us to realise that this paradox is wrong. As a result, we can prove our position quite easily, by drawing the graph of the distances in time made by both racers. However, for a non-mathematician, it would be not so easy to explain where this paradox lies in. Yet such interest and efforts to explain the incomprehensible lead us to incredibly interesting concepts, paradoxes and examples of the set theory. I thus think that efforts to explain (or vice versa – to deny) theories, positions or opinions that you don’t believe in or don’t’ understand at all by providing exhaustive logical argumentation, is always a much more “profitable” process for yourself than just efforts to reasonably explain what you like, understand, and what is close to you.

At this point, I should revert to the Bradford context and try to explain why, at that time, I did not understand the dissonance between me and Bradford’s Muslims. I certainly do not want to apply my observations to the Muslim community worldwide, the entire Islamic religion, but to the sample I had the chance to observe for about a half-year in Bradford rather.

It is not at all difficult to specify basic things and processes associated with Bradford Muslims, whom I have found to be completely alien to me. They include their very unattractive shops, cheap and low quality goods, a lack of culinary imagination and overall poor understanding of gastronomy, even at local Muslims’ higher-class restaurants, the extremely non-aesthetic clothing of local Muslims, etc. I remember myself thinking at that time that if I were to describe all of these observations in short phrases, I would say that “Bradford Muslims’ energy is very close to earth, very close to ground, ‘very earthly’”. Such phrases are certainly too abstract, so I tried to analyse what lies underneath them.

It seems to me that one of the major objectives in every human’s life should be breaking as many social constructs as possible throughout their lifetime. Breaking of social constructs allows a human being to reduce the influence of the social environment on them and thus to take a step closer to giving meaning to one’s own character features more precisely, to the development of skills adequate to one’s own body, and to better cognition of one’s self in general. As an example, I know a man who was born probably not into a most harmonious family, not in Lithuania’s best city, and not in this city’s best district. Under the influence of such social circumstances, he made friends with his playmates in the yard. Influenced by them, he began stealing until eventually found himself in prison in Sweden. In other words, the above-named man did not manage to cope with one of the first social constructs in his life – the influence of his playmates in the yard. Had this man conceived that he was in no way responsible for his family, place of birth, and the people who surrounded him at the early stage of his life, he would have begun developing the skill of breaking social constructs. It means, that man would have been able to make use of the possibilities life had offered him in a much better way than just spending his days in a tight prison cell.

What do Bradford Muslims have to do with the breaking of social constructs? It seems to me that any religion should be an instrument helping a human being to grow, to have a critical perspective on the world, and to break social constructs. However, the way a significant portion of Muslims residing in Bradford interpret Islam, in my opinion, exactly prevents personal growth. A great number of Muslims I have seen, since birth, accept such social constructs as the construct of women’s adequate clothing, praying for the sake of praying a set number of times per day, etc. without any questioning at all. In no way do I say that Bradford Muslims should escape from the obligations of their religion. I rather mean that Muslims’ relationship with their religious obligations should be much closer, more sophisticated, and less straightforward. By calling their obligations into question, Muslims would be able to understand the fundamental truths of life actually underlying each of them. For example, the essence of the obligation to pray five times per day is just probably an aim for a human being to be as self-reflective as possible. So, one sincere prayer, one sincere self-reflection per day would probably give a person many more answers than such enforced number of them which gradually leads to automation, motoric actions rather than sincerity.

Hence, similarly to the above-named case of the man who was imprisoned in Sweden, Bradford Muslims, since the early stage of their life, do not develop the skill of breaking social constructs at all either. How does this relate to my phrases that “Bradford Muslims’ energy is very close to earth, very close to the ground, ‘very earthly’ ”?

What human works, creations do we mostly characterise as “heavenly” or “cosmic”? I think, we so characterise works that require an enormously high general intelligence. As an example, a man with a particularly high general intelligence in mathematics, music, social sciences (not necessarily specific knowledge in a specific field, sometimes – just an extraordinarily good intuition in those fields) happens to create an incredible composition which not only meets all of the rules of harmony in music, the laws of the most aesthetic mathematical proportions, but also combines and expresses the thoughts of a specific social group.

Hence, talking about high general personal intelligence, as an expression of “something which is cosmic”, the main precondition for the formation and development of personal intellect is just sincere and maximum calling of the world into question. As the Muslims I have seen do not develop the skills of breaking social constructs, their critical perspective on the world becomes very static, minimum and narrow, as it only takes place through the prism of their religion. This, certainly, also leads to the non-development of general intellect. Which in turn results in the things already mentioned above: a lack of imagination, no idea of how to make high-quality food, a lack of the feeling of aesthetics whatsoever, etc.

Towards the autumn, my studies at the University of Leeds were gradually taking pace. To cut the long story short, as most of typical University study programmes, this one (MA in Electronic and Computer Music), too, consisted of theory and practice. During my theory courses, I studied and analysed different historical contexts of electronic and electroacoustic music, specific historical practices and techniques used by music creators. During the practical part of my studies, I mainly studied how to use Max 7 (Max/MSP) musical software. Most of you have probably seen pictures or video recordings of professional sound engineers or music producers sitting in luxury music studios and working with very aesthetic-looking audio processing programmes. You can see a great many of channels, buttons, sound waves, etc. in those pictures or video recordings. Max/MSP is a slightly “deeper” alternative for the programmes you have seen. I define it as “deeper” since you can see in it all the mathematical laws, connections, links, numbers, parameters present beneath those highly aesthetic audio visualisations. Hence, you have a possibility to unravel what mathematical laws, parameters and connections are present in absolutely any musical process or instrument.

I used both the theory of the studies and my skills of working with Max 7 for my projects and creations relating to the fields I had known prior to my studies: the art of Scottish Bagpipes, Tap Dancing, mathematics, the guitar, etc. Thus, all this mix of fields and skills was employed mainly in the field of sonification of mathematics already mentioned before. In this field, I tried to express, to sonify various mathematical theorems, laws and processes through the sounds of the bagpipes, tap dancing, and other musical processes. All this for the sake of mathematics, to make it easier to understand, more effective, and more interesting to those who take an interest in it or study it.

At the very beginning of my studies at the University, I noticed, in one of its web pages, that company NUGEN Audio was looking for a developer. To put it briefly, NUGEN Audio is a Leeds based company which develops music software for sound engineers and music producers. It was founded by two friends: Paul Tapper, who, prior to founding this company, was a developer holding a PhD in Mathematics and who developed the absolutely iconic computer game Worms, whereas Jon Schorah was a professional DJ who had received the education of architect. Over 15 years of being in operation, NUGEN Audio has significantly pushed itself forward in the music and audio industry: countless world-level music producers, sound engineers of such musical artists as Coldplay, Bjork, Norah Jones, etc., sound engineers of the most famous films in the world: American Beauty, American History X, Trainspotting 2, etc., began using its products.

I did not thus have to go deep into myself to look for a motivation to become a part of NUGEN Audio. Nevertheless, given the company’s achievements and the fact that it was my first effort to get employed in the island, after sending my CV, a motivation letter and performing a few programming tests online, I did not expect much. However, to my great surprise, representatives of NUGEN Audio invited me for an interview.

The meeting with the above-named founders of NUGEN Audio went incredibly smoothly: we understood each other’s contexts and felt each other’s character and energy perfectly well. So, making my way towards the University after the interview, I was deeply upset. It seemed to me, I have just experienced that, according to the Domantas Razauskas’ tree root concept mentioned at the beginning of this essay - I was connected in Leeds with some people through my thoughts, observations, and philosophy of life. I was feeling rather sad though since my rational mind said that there was a very low probability of the founders of NUGEN Audio choosing me for this position (as it turned out later, out of about 50 applicants).

There were a few issues that was making my application unlikely successful. Thinking rationally - Great Britain’s entire social system is based on the references principle. This means that you should hand in a reference from your previous employers, colleagues or lecturers to people who don’t know you – your potential lecturers, employers or colleagues. I had just set foot in the island and so no Brit could give a reference to such a crazy a Lithuanian at that time.

On the top of that, my rational mind said that one social difference which surfaced during my interview might become a barrier for me being chosen by NUGEN Audio. The ad about the possibility to work in NUGEN Audio also indicated potential wage within specified range. When asked what wage within that range I would expect, I said that, given the huge risk the company would take by employing this strange Lithuanian with no references, I would expect a wage much lower than the specified range – just the minimum wage of United Kingdom. This was the only off-key moment during my interview – the founders of NUGEN Audio did not understand my expectations at all. According to them, the mere fact of me having been invited for an interview meant that I was worth a wage within the above-named range. Thus, the expressed expectation of a minimum wage was, they said, an extremely unprofessional action contradicting social laws.

Yet the fears of my rational mind were nothing compared to the fearlessness of those two great men – Paul Tapper and Jon Schorah: they have proven the existence and the greatness of the tree root concept. Just one CV sent, just one job interview since the beginning of my stay in the island – and the existence of the essential link between people overshadowed all social laws, all the probabilities created by those laws.

Full-time working regime naturally changed my academic life somewhat. I had to fit in time so closely that often, during my lunch time, I would just take to my heels to catch a taxi to the University to show up at the lectures, for a brief talk with the lecturers, and overall to show that I am safe and sound. Such lifestyle increasingly reminded me of one scene from the 1976 Martin Scorsese’s legendary film Taxi Driver. A US presidential candidate with his escort once sat into a taxi driven by the films’ main character Travis played brilliantly by Robert De Niro, who at that time was starting out on his promising career. Travis recognises the US Presidential candidate and starts a conversation with him. In a short while, the presidential candidate utters that he has found out and learnt about America much more by travelling it by taxis rather than by luxury limousines. I must admit that if I were asked which tourism agency or which university would help you to know England in the best possible way, I would answer that it would be an extensive use of England’s taxis.

Full-time working regime, full-time studies, and being a father full-time were testing my body for its physical limits. Throughout December, I survived being seriously ill – there was not a single moment for my body to recover. However, after succeeding to finish the first semester of my studies, at the beginning of January, I eventually could take some fresh air. My female companion P., who was to arrive for a week’s stay early in January, was supposed to cheer us up. While we have always been in close contact with P., we had not met in physical terms for some years as she had travelled the South American jungle for a few years and met with some local shamans.

I usually avoid talking about important events in my life with people close to me online or by phone. I think meeting face to face is a much more sophisticated way of communication. Therefore, I was impatient to meet P. not just to hear about all of her adventures and experiences in South America, but also to share with her the message of me being a father. If I happened to meet some friend or acquaintance of mine in the streets and share this message, those who knew me and my lifestyle could hardly believe this news. Therefore, as a taxi was driving me and P. towards my home in Bradford, I expected an unusually expressive reaction from P. when she sees my daughter.

I entered the house, turned to P. and said that the surprise I had mentioned to her was the fact of me having a daughter. However, I was struck by P.’s reaction – not a single muscle of her face moved. P. just quietly unbuttoned her coat and said, “Congratulations, me too”. I saw P.’s huge belly that she was hiding under her loose coat and both of us started laughing incessantly. Actually, the least thing both I and P. had always sought from our environment was social security and stability. We always saw the meaning of life somewhat elsewhere. Being well aware of such paradoxes, challenges of life, and of its beautiful moments, we thus kept on laughing for a good dozen of minutes.

All of us decided to spend three nights in Whitby. This town of magnificent beauty I already mentioned herein is located on the shores of the Northern Sea and is known for its close associations with the book Dracula by Bram Stoker. Part of this book was written as Stoker was spending his summers exactly in Whitby, while part of the plot in the book itself also develops namely in Whitby.

The discussion we had during this stay in Whitby in one of the most loved venues of mine and L., the tea room Marie Antoinette, is probably the most memorable recollection of our stay there. The best introduction into this discussion of ours is probably the thought of the legendary musician Brian Eno expressed during one discussion which took place in the Church of St Clements in London. According to this creator, we overestimate the concept of genius. According to him, we should focus much more on the concept of scenious. Scenious is actually a concept devised by Eno in this context. However, both in terms of its consonance with the word genius and the meaning applied by Eno to this word, the word scenious becomes a real gem in this context.

Eno asserts that some specific trend, some idea in art or science is always represented and developed by a huge human community. Only when that idea or trend has been sufficiently developed, when it matures, is that final cherry being picked by one human being we begin identifying that trend or idea with. Such social process is certainly not really fair taking into consideration the many people who had developed that trend or an idea. As an example, there is a great documentary, Marley, about the way Bob Marley has made the reggae music genre and reggae culture famous in the world. In this film, if you paid attention how rich and significant reggae culture and scene had existed in Jamaica before it appeared on the global scene, that there had been extremely talented musicians and producers (Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, etc.) who had developed this music genre before that, this will make you realise that Bob Marley’s role in this music and cultural trend is weighty, but not essential. Hence, the word scenious, which, if translated directly, would mean something like scenic, directs attention namely to the significance of the scene in any trend, of the community in any trend, and concurrently, through its consonance, teases the concept of genius.

How does this relate to our discussion in Whitby? Well, we had a hot discussion there about how much important, for a genius, is the feeling, the ability to “smell” a specific geographical location of the world where a “scene” could be formed so he could realise his ideas and creative work to the maximum extent. I once believed that a genius can create miracles without leaving his dark room. Now, it seems to me that each man with the ambition of at least getting close to the definition of genius must have developed at least a minimum ability to “smell” a specific geographical location of the world where they could find themselves at the apex of their trend, their “scene”. We would hardly know about Jurgis Mačiūnas or Jonas Mekas today if it were not for their geographical location – New York, where the Fluxus movement then matured.

The founders of NUGEN Audio, Paul and Jon, travel the world extensively on a permanent basis. At least 15-20 times per year they fly to the most distant corners of the world such as Japan, the USA, etc. to take part in various music and audio industry conferences, fairs and conventions. The company has an official regulation that each employee of NUGEN Audio must at least once travel to one of such conventions with Paul and Jon. As I had already warmed my feet in the company and spring came imperceptibly, I found out that the three of us would be going to the AES (Audio Engineering Society) Convention in Berlin.

This was to be the first business trip in my life and thus totally different from my former trip experiences and habits. Symbolically, Berlin itself was one of the first cities I once, at the age of 18, went to with a few companions to play music in the streets, spend nights under bridges, and drink wine (for more information about this, read my essay Abroad). And, look, – exactly after ten years, I was coming back to this magnificent city, already as part of an important player in the music industry, staying in one of the best hotels in Berlin, and eating at Berlin’s best restaurants.

Indeed, this trip was absolutely refreshing after nine so intense months spent in the island. For the most part of the day, I would listen to the world’s best audio experts’ lectures, which not only enhanced my professionalism with specific audio skills, but expanded my understanding of the audio field as well. In-between the lectures, I would sometimes go to help Paul and Jon, who had an own stand in this convention and communicated with their clients and colleagues in the industry.

There were indeed many lectures that caused a thrill of excitement in me. I think I should extend on Eddy B. Brixen’s lecture on audio forensics, which most Lithuanians (as well as a large portion of people in the world) must know about from the TV series CSI. This field is about the way audio records and their reproduction help identify crime details and circumstances. It was interesting to build up my own picture of this field in my head – much more realistic than that shown in the CSI series.

Murder investigation is nowadays not at all the major object of the application of audio forensics. Nowadays, it is musicology rather. In other words, more and more cases that go to court and that requires involvement of experts in audio forensics are related to such questions as “Who of the music creators owns some specific audio sample and who is just using it in their piece of music as a theft”, “Whether the audio record heard in the piece of music has been stolen from some existing audio database”, etc. Brixen, who is often hired as an independent expert in audio forensics in legal proceedings, was once involved in his practice in an interesting case related namely to musicology too. Some Danish music producers devised a plan for making money by selling the same composition (the same audio track without the vocal part) to two Danish singers, Christine Milton and Jamelia. Of course, after some time, one of the singers applied to court with a claim that her audio track has been “stolen” by the other creator. After a thorough analysis of the two audio records, it finally turned out that none of the singers was guilty and that this had to do with the greediness of the above-named producers.

That audio forensics contains yet another myth. Almost at all times, it involves particularly long and very thorough work to reach the final conclusion on the basis of audio recordings. However, this conclusion of audio forensics specialist will not always be taken for granted in court by the judge. Presentation of results and their argumentation in court are no less important. In such cases, every detail matters: whether the court hall premises are adequate for listening to specific audio records in terms of acoustics, whether the audio records can be heard well by court participants who have a less sharp ear, whether any findings of audio forensics were based on scientific papers and literature, etc. Therefore, experts in audio forensics often provide a possibility for court participants to listen to audio proof by means of headphones.

However, Brixen himself avoids presentation of audio records on headphones as much as possible owing to its so-called ”bad hair” effects. During his lecture, Brixen highlighted at least a couple of times, and meant it, that female judges very often get nervous if they have to listen to audio records on headphones because this ruins their fancy hairdos. Which is not funny at all since audio records, under such circumstances, could be listened to very carelessly, without paying attention to the small details.

What I am trying to tell by this weird context of judge hairdos? Yes, an expert of audio forensics nearly always works in court as an independent expert who is only provided with audio records and certain circumstances of a specific event, without any data of the participants in that case or other excess data of the case or the event. Nevertheless, an expert of audio forensics must act in the same manner as a top-level lawyer – not only to be an expert in their field, but also to thoroughly analyse all of the circumstances related to that specific case that might affect its result, such as the acoustics in the court hall, characteristics of the judge, etc. Of course, an expert in audio forensics differs from a lawyer in that the latter always has some interests in a case, whereas an expert in audio forensics carries out a thorough examination for the sake of as representative reproduction of the circumstances of an event as possible irrespective of who those reproduced circumstances will be favourable to.

During his career, Brixen had more than one possibility to contribute to the unravelling of extremely serious and complicated cases. For example, a woman who was being raped once called the police to notify of the crime being committed. During her talk with the police, she, fortunately, managed to escape from the flat where she was raped. Since the woman was intoxicated with drugs and experienced a shock, she did not remember where that flat was nor its layout or size, etc. Based on the acoustics of her talk with the police and on how it was changing as she tried to escape from the flat, Brixen had to identify the flat’s layout and its potential location.

Brixen’s lecture was a mixture of a number of other unbelievable contexts too. Indeed, there are quite few experts of audio forensics in the world, and most of them often conceal (or are obliged to conceal) the specificity of their work so it is not manipulated freely for criminal purposes. Thus it was a great pleasure and privilege for me to listen to a lecture delivered by Brixen. Of course, the lectures of other audio professionals were no less contextual, interesting and fruitful. Irrespective of the field audio professionals might be working in – criminology, music producing, events organisation, etc. – their work always stay away from the spotlight. So, hearing the stories about the especially interesting specificity of the work of audio experts in public is a rare opportunity. Nevertheless, I should probably take control of myself and not expand on the contexts from other lectures attended since this essay would start being reminiscent of an audio treatise:)

Paul and Jon really definitely know how to enjoy life, so we were regular visitors to Berlin’s restaurants and bars every evening and night. While in Berlin, you can hardly skip such phenomenon as the BRLO Brewhouse – a bar/brewery constructed from 38 sea containers in the middle of the fields. It is a perfect representation of Berlin as it is today. I just have to warn you to enjoy the beer in BRLO Brewhouse responsibly since owing to this brewery’s surrealist environment, you just don’t notice how the time passes and what is the number of pints you have already consumed:)

During this trip, the founders of NUGEN Audio acquainted me with many people within the music industry. Acquaintance with one of the world’s best audio engineers, Mandy Parnell, working with such groups and creators as Bjork, Sigur Ros and having a particularly close relationship with NUGEN Audio, was probably the most memorable. Having found myself so close to Iceland’s majestic tree roots, I was rejoicing at the effectiveness of the tree concept.

After such fresh, gripping and incessant flow of life in Berlin, I felt miserable to return to the island. Though I don’t believe that Berlin, once it captures a person at least once, would release that person for good easily.

After about a year and a half spent in Leeds, as my studies were nearing the end, we felt it was time to leave the island. Our plan was to travel the world somewhat more widely (probably by the Trans- Siberian Railway further eastwards), so I decided to inquire the NUGEN Audio men about the possibility for me to continue work from any corner of the world. Paul and Jon, as usually, supported me, agreeing with this offer of mine. So L. and I began slowly working out our routes across the world. However, the world laughed at us: a few days after my agreement with the NUGEN Audio men, we found out that L. was pregnant and we will soon have a son. Consequently, we had to change our geographically wide intentions into a more modest plan to travel Spain and Portugal by trains for a few months.

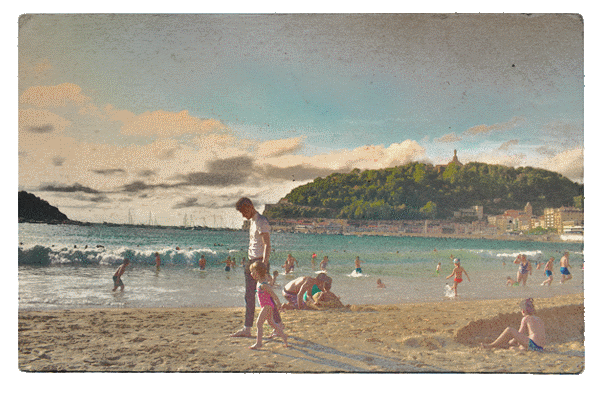

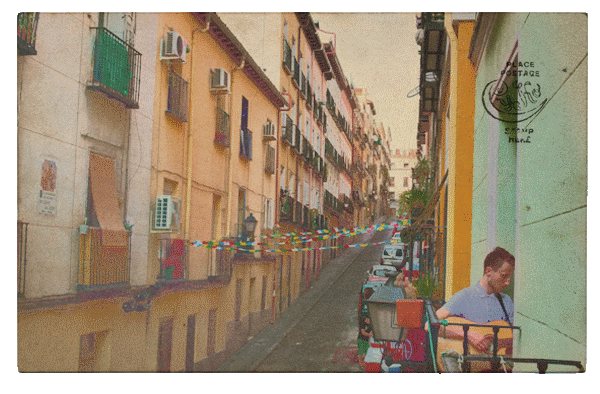

As we set out on our journey from United Kingdom, we carried all of our countless personal belongings acquired in the island with us. The major part of them was consisted of my instruments – a set of Scottish Bagpipes, a guitar, Tap Dancing shoes, massive portable/constructible parts of the tap dance floor, different music technology equipment, etc. Though I had planned to show off as a musician from time to time, I managed to do this on very rare occasions as L. and I were creating this Internet home – vienozmogausrespublika.lt during most of our journey. We visited a number of cities during our journey spending some time there: Bordeaux (France), San Sebastian (Spain), Bilbao (Spain), Madrid (Spain), Lisbon (Portugal), and Porto (Portugal). It was thus extremely difficult to carry all those suitcases weighing tens of kilograms with us – from city to city, home to home, train to train.

During the final days of our journey, I tried to reflect on it. For a moment, I had a feeling of total meaninglessness, trying to ask myself why I was carrying all those music aggregates and instruments with me. This neither had brought us any income nor helped our journey or everyday life in any way. Yet, in a moment, S.’s concept of belief mentioned at the beginning of this essay came to my mind, reminding me that it consists of 100% of belief and 0% of expectation. I thus calmed down, having realised that one has almost no choice in such situations – just to keep carrying calmly ideas that are close to your own body, both their physical representations (in this case – suitcases with instruments) and absolute belief in such ideas.

If I took this self-reflection on the journey in absolute terms, I would say that all the areas that I have real passion for, i.e. mathematical philosophy, mathematical history, writing, the Scottish bagpipes, the guitar, singing, tap dancing, have always been close to me without a grain of complaining. Involvement in these areas has always been so dear to my heart that it has never occurred to me to require at least a penny from the public for spending so much time and energy in them. Young medics of Lithuania would certainly disagree with me. Take, e.g., medical movements that have been taking place in Lithuania lately or my discussions with my close friends medics: you incessantly hear their opinion that the public owes them a lot immediately after they have read a few books during their studies. So, it seems that young medics’ belief in their sphere consists of maximum expectation and minimum belief in the meaning of medicine and in the meaning of their own involvement in it in general. We seem to have a concept quite opposite to that of S.’s.

Such, in my view, wrong relationship with one’s chosen path leads to yet another issue. The problem is that this is where the public’s standard thinking arises from when, choosing a certain way of life, we fail to understand what is the main object of the way of life chosen, the main matter we will have to deal with for the rest of our life. As an example, I hear quite extensive argumentation from medical persons who have chosen to specialise in the field of cardiology that their choice was determined by the profitability of this branch of medicine. In other words, the rationale of such medics behind the choice of this branch of medicine has little to do with its main object, main matter – the heart. At least I would expect from medical persons within this branch such absolute arguments as “I have chosen this branch since the heart is the most often mentioned human organ in the books, so I want to devote my life to finding out why this organ is so exceptional and special” or “I have chosen this branch because the heart is the most mystified human organ by man, so I want to devote my life to cognising this organ and demystifying it”, etc. Instead, medical persons begin associating cardiology not at all with the heart but with another matter, money. Choosing money, as the central object in one’s life, is not a bad thing in itself. If, of course, one chooses such spheres as finance or economics, which directly deal with money as their central object or matter.

I am a very happy man as music has always been to me about the sound and harmony. Nevertheless, I am aware of plenty of people who claim being in music just because they have been dreaming of performing at Wembley Stadium or Glastonbury Festival (probably the largest and most significant music festival in the world). To put it in another way, such people, in choosing the stadium or England’s green field (where the Glastonbury Festival takes place) as their primary matter, should actually consider about the career of a football player or an agriculturalist rather than that of a musician:) Darius Žvirblis, one of the most genius all-time creators of Lithuanian music, teases people who see Wembley stadiums as the central object in their life in an even more sophisticated and ironic manner, in his song Padarom (Let’s Do It).

If you do not know Darius Žvirblis’ music, I strongly recommend that you should begin your acquaintance with this author from his other great pieces such as Jeronimui, Eduardui ir Vyriškiui su Abitu, Sako, Buvom Svetimi or Kas Įvyko? from the same album Pretenzija as the above named Padarom: Darius Žvirblis – Pretenzija. Or, even better, from such genius album of the legendary group Atika (led by Darius Žirblis himself in the past) as Po Visko, without which I cannot imagine the Lithuanian alternative music history, which contains masterpieces of lithuanian alternative music such as Tu Esi (Ir Šito Gana), Sekmadieniais Lyja, Ji Pabučiuos, Airiškas Migracinis, Kormoranams Neramu: Atika – Po Visko. It seems to me that Darius Žvirblis is generally one of the few creators of Lithuanian music whose music has always been about belief. Music in which I’ve never heard any whining, complaining or expectation.

So there’s nothing else left to say at this moment of my life, my dears. I wish you pleasant hanging on the point of intersection of a horizontal and vertical lines.

I am not being touched by the essence and the meaning of public celebrations usually – the New Year, Saint Valentine’s Day, Easter, etc. The main ideas of these celebrations and the dates representing these ideas mostly quite disagree with the rhythm of my body. I am rarely eager to “squeeze” love out of me on Saint Valentine’s or to revive during Easter. Yet I adore celebrating silent victories against myself – the reading of a fundamental book, comprehension of a complex theorem, creation of a good composition, etc.

This also applies to silent challenges for myself on the way: I am always willing to give a meaning to them, to mark them in some way. Giving some importance to the upcoming challenges would allow to better recall the way I sensed before addressing a complex objective. Probably, this is why I faced one of the greatest challenges in my life wearing my most expensive shirt and shoes. I wanted to give a meaning to my fight of the fear of the upcoming challenge and to meet potential hardships awaiting me with pride.

I was travelling to England with 1,000 pounds in my pocket to study the Masters of Electronic and Computer Music and overall to conquer this land. A situation not over contextualised or significant in any way at first sight – just like another subplot in Marius Ivaškevičius’ play Išvarymas (Expulsion) about emigration. Yet it was not that simple as I was responsible for two other women, one of whom was just one-year-old. They were jo join me and my plans of conquering the world in the island in a month’s time, so I had to materialise my determination and energy quickly.

The conquering of the island was to begin in Leeds – United Kingdom’s third largest city by population (after London and Birmingham), which is located in the middle of the island. Because of my limited finances, I was planning to start my existence in England with living in a tent. However, rainy weather in Lithuania the last night before the trip somewhat suppressed my desire to subject my body to living in similar conditions on the island. So the last night I booked a hostel for just ten pounds or so per night, which was located in the village of Haworth some 30 kilometres from Leeds.

The island reacted to my most expensive shirt with a hysteric laugh: as soon as I landed, I found myself in the middle of a storm. As I booked the hostel in the remote village as late as the night before, I had not enough time to find out how to get to it. By asking people and changing means of transport, I was approaching my destination somehow. Midnight came unnoticed though, while I was standing in the rain, at a distance to my destination of slightly less than ten kilometres.

I had no way out of this situation other than pulling my suitcase weighing almost 30 kg, carrying a heavy guitar case, which contained my guitar and countless household appliances in addition, down the narrow roads of the village in the storm. Shortly, my suitcase ripped, and raindrops were dripping from me all over. Angry, I started questioning my existence on the island and my belief in what I was doing there. For the first time, my mind realised the odds I will have to play against while in England. I thought that I was in danger of getting remote from music and that the island’s inhospitableness might bring me to some factory to be able to survive.

Nevertheless, both that and other nights, one context that I have already mentioned in my stories was leading me further. A great Lithuanian musician and music critic, Domantas Razauskas, during one of his concerts, gave a comparison which is close to my philosophy. He said, take a forest full of trees. It seems, nothing makes those trees interrelated; however, the roots of some of them are intertwined particularly closely. Sometimes, even quite remote trees can have roots intertwining closer than the roots of those growing nearby. According to Razauskas, in a similar way, people, too, are related with one another through invisible bonds in the physical world. Consequently, even people who are very remote one from the other (in every aspect: cultural, social, geographical, etc.) can have much more in common than some two people living close by.

Yes, my mind did perfectly realise all the odds I will have to fight, but I did not cease to strongly believe that I was interrelated “through roots” with some of the local people. The people who will comprehend all the contexts I am bringing, who will give me an impulse, and will help me tame this island.

In this specific situation, I defined for myself ‘belief’, making use of the above-named concept of tree roots. Yet it seems to me that each human being has a secreted adaptation of the dilemma of belief in their life, in the areas they operate in. Those adaptations do not necessarily have to relate to religion, God or similar concepts in any way. For example, in the philosophy of mathematics and in mathematics in general, one of fundamentals issues dealt with, one of fundamental dilemmas is: Does mathematics exist independently of man and the man just discovers, reveals those laws of mathematics that exist by themselves or does such absolute independent mathematics not exist at all and the man just creates it little by little, theorem by theorem?

It seems to me that this underlying mathematical issue is nothing but a sophisticated adaptation of the dilemma of belief and of belief in God in general in the mathematical context. Now, for instance, supporters of the independent existence of mathematics (also known as representatives of mathematical platonism) basically take up the same position as those who believe in God: There exists something independently of us, something we are too little to perceive, to see or to comprehend.

A year ago, I happened to talk with Rimas Norvaiša, a Lithuanian mathematician and philosopher of mathematics of the older generation, about his approach to the above-named mathematical dilemma. According to him, he began his career in mathematics believing that mathematics exists independently of man, but, gradually, he found himself on the opposite side of the barricade. Indeed, most people I know, irrespective of the adaptation of their dilemma of belief, have almost an identical approach to the dilemma of belief as Norvaiša. In the early stage of life, people believe until they become older when they gradually take up the opposite position. Such approach to one’s own dilemma of belief has always seemed logical to me, but not completely right. The conception of belief of the politician and theologist S. she shared with me answered many questions I had about the approach to one’s own belief.

S.’s conception of belief is inevitably associated with the central symbol of Christianity – the cross. When I talk or discuss about belief, I usually avoid using any keywords associated with some specific religion, such as Jesus, Muhammad, Koran and the like. I also try not to use general words that are often encountered in the contexts of religious studies, such as sinful, Lord, etc. I notice that the use of these keywords very often enrages people and prevents most discussions on the topic of belief. I avoid these contexts not only because of other people, but myself as well. I, too, find such keywords and contexts too straightforward, unsubtle, unsophisticated, and incomprehensive in the context of the dilemma of belief. Similar to some of the nightmarish Hollywood films that are only capable of invoking zombies, guns, death or other similar themes to depict evil. However, S.’s conception of belief is so putting everything in their place that it would be a shame not to include it in here.

According to S., the cross can be interpreted as follows: its vertical (longer) part represents the world as it should be, while its horizontal (shorter) part represents the world as it is. To cut the long story short, comparing the lengths of the two parts of the cross is turns out that, in the real world, there will inevitably always be much less positivity, happiness, joy and logic than there could/should be. While every human being is hanging on the cross point of the vertical and horizontal lines all their life and the way they, hanging there, cope with this proportion: The world is as it is/The world as it should be, is a belief.

Why is this conception so important and how does it relate to the contexts I mentioned before?

I tend to believe that the absolute majority of the adaptations of the dilemmas of belief contain not just belief, but expectation as well. For example, a large proportion of believers in God prey for a good fortune for themselves and their environment. Yet, when such good fortune for them and their family and friends never happens, such people begin losing general belief in God. Or, for example, a large proportion of people supporting some football team do expect a victory for it and a fun time for themselves at the same time. However, if the team loses steadily, such people gradually give up belief in that specific team. Consequently, that, although small proportion of expectation in general belief, over time markedly weakens general belief in something as well.

Meanwhile, S.’s concept is an absolute nugget: it consists of 100% of belief and 0% of expectation since the essence of this concept is that it is always worse than it should be, so there’s nothing to expect.

To revert to my trip, my belief during the trip as an expression of the above-named tree root concept undoubtedly contains a very high proportion of the expectation of specific benefits for me as well. Yet my aim should certainly be proceeding to S.’s above-named conception – belief without a grain of expectation. I guess, I should demonstrate my solidarity with the fans of Lithuania’s football team at some point:)

I reached my hostel as late as 3 o’clock in the night, knocking on its door and waiting for someone to pick up the phone for another half-hour. Next day after the nightmare night, I felt more dead than alive. Nevertheless, towards an evening, I went out to look round and was totally enchanted by this idyllic English village. It turned out that Haworth is famous for the fact that the world-famous writer Charlotte Bronte, mainly known as the author of the novel Jane Eyre, lived, wrote, and died there. Inspired by this fact and with relatively much time at my disposal left from the search for accommodation and submission of the documents for my studies, I spent a good couple of weeks wandering around Haworth and writing. It was in Haworth that my story Questioning published on this site, saw daylight.

No less than Haworth, I was impressed by the hostel I was staying at. Despite its extraordinarily low cost, it was housed in an ancient Victorian manor house with stunning aesthetics. This experience was my first coming in touch with one especially remarkable phenomenon of England.

England has a network of hostels known as YHA (Youth Hostels Association). This network’s hostels (joining about several hundred hostels), as in Haworth, are established in ancient manors, castles, barns, and other special venues. This network is a charity organisation which gives all of its profits from accommodation namely for the restoration and maintenance of buildings of the ancient architecture. Accordingly, the clients of this network are given an opportunity to stay in these exclusive buildings with incredible aesthetics for a relatively lower price than such an opportunity would cost on England’s market.